England just had its second-worst harvest on record. As far as I can tell, those records go back to the early 1800s. Wheat fell 21 percent. Barley fell 26 percent. Across the board, it was 15 percent. (The worst harvest happened in 1983.) Months of torrential rains wiped out crops. A new pattern has descended. The fall is too wet. The spring is too dry. The summer is too hot. That’s what a climate crisis does. It turns centuries of predictable weather patterns upside down.

Floods are routinely destroying rice crops around the world. So far, countries are managing to skid through by planting more and harvesting early. Let’s face it, we’re fighting a losing battle here.

Meanwhile, in the U.S., a piece in Successful Farming confirms what I saw while going through years of crop reports. Wheat production has declined over the last two decades due to drought, heat, and severe weather. Farmers are giving up and shifting toward soybeans and corn. It’s more profitable, and most of it goes toward animal feed or fuel. Not that much goes into food.

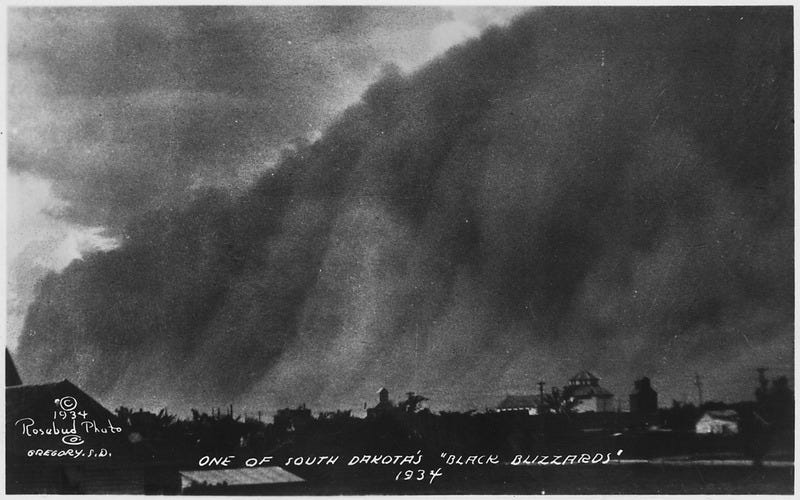

Your average American probably doesn’t think much about famine, even as they complain about the price of burritos at Chipotle and fail to connect the dots, that the climate crisis is already hitting them. It hit us back in the 1930s, too, when overfarming turned a drought-prone region into a dust bowl that lasted a decade, followed by more severe droughts in the 1950s. Things didn’t get better until we overhauled our agriculture and irrigation practices.

I guess our friends skipped that week in history class.

Just like many other countries, the U.S. is staving off collapse by depleting what’s left of the land’s resources. That includes pumping the Ogallala Aquifer dry. As a PBS special explains, the Great Plains region produces nearly a quarter of our crops and almost half of our beef. Farmers and surveyors there put it plainly, “What we’re doing now is not sustainable… We have to bring groundwater back into balance, or there’s going to be serious disruptions of our food system.”

Some farmers are using their heads and moving to sorghum and amaranth, which can deal with heat and drought. They’re also installing drip irrigation systems and working harder to conserve water. That’ll help, but it doesn’t change one hard fact. According to studies covered in Nature, the plains are entering an era of megadroughts, the worst in a thousand years.

Scientists call it a “fundamental shift.”

Look at history, and you see that famines have happened all over the world. As Nobel laureate Amartya Sen first wrote in his 1981 book Poverty and Famines, the worst famines and food shortages in the modern era had less to do with agriculture and more to do with “entitlement,” reckless decisions made by policymakers that resulted in mass starvation. Sen talks about the Bengal famine of 1943, the Ethiopian famine of 1973-74, and the Bangladesh famine of 1974. But you also see it in the Chinese famine of the 1950s, The Irish famine of 1840s and 1850s, and the Ukrainian famine of the 1930s. There was food. It was just too expensive for poor people, and the rich didn’t care. You even saw the same attitude in the U.S. during the first part of the Great Depression, before Roosevelt stepped in.

American politicians were more scared of fostering “communism” than helping the food insecure. They thought chronic hunger built character.

Amartya Sen makes a bold point about famine that took a while to catch on, that a free and fair press plays a vital role in holding leaders accountable, and that tends to blunt the root cause of famine—greed. Famines result from the failed policies of dictators who don’t have to worry about accountability.

If you want a recent example of that, U.S. policymakers were recently caught leasing Arizona land to Saudia Arabian farmers to grow alfalfa for dairy cows, something banned in their own country. This happened during severe droughts. The governor refused to install meters to track water use.

He was “afraid.”

So if you’re wondering if your elected officials would let you die of hunger and thirst while giving your food and water away to international corporations, the answer is a yes, for as long as they can. This would be yet another reason why the super rich are buying up newspapers and directing them to minimize global catastrophes. They just hate being held accountable.

The famines of the last century were the result of failed policy. The famines of the new century will see the upending of agriculture as we know it. So it’s going to be a mix of ecological overshoot, true crop failure, greed, and lack of accountability. Given all of that, you’re not crazy if you’ve ever thought about storing food for rough times. It raises a lot of questions, though.

Is it even worth doing?

How?